by Jason Anthony Akerman

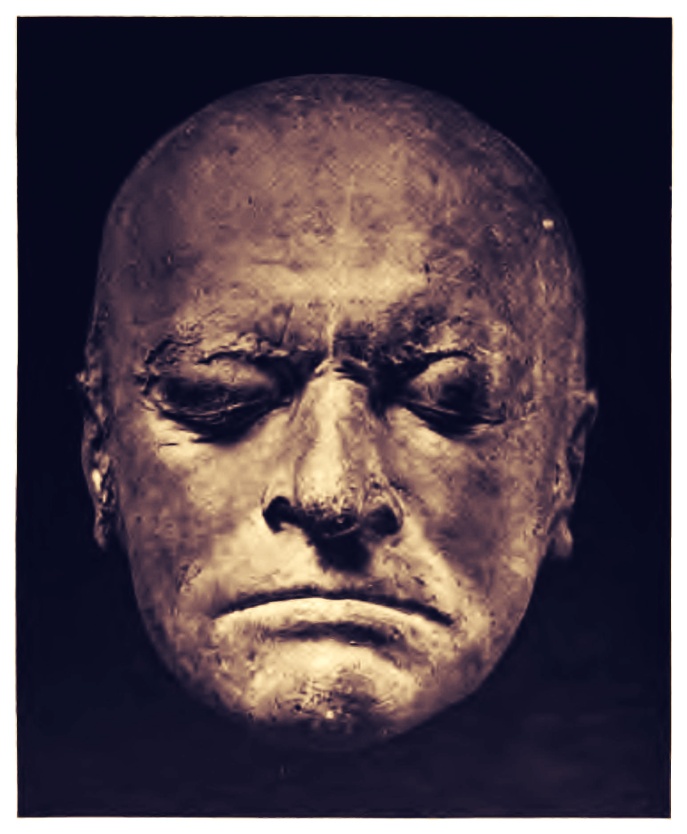

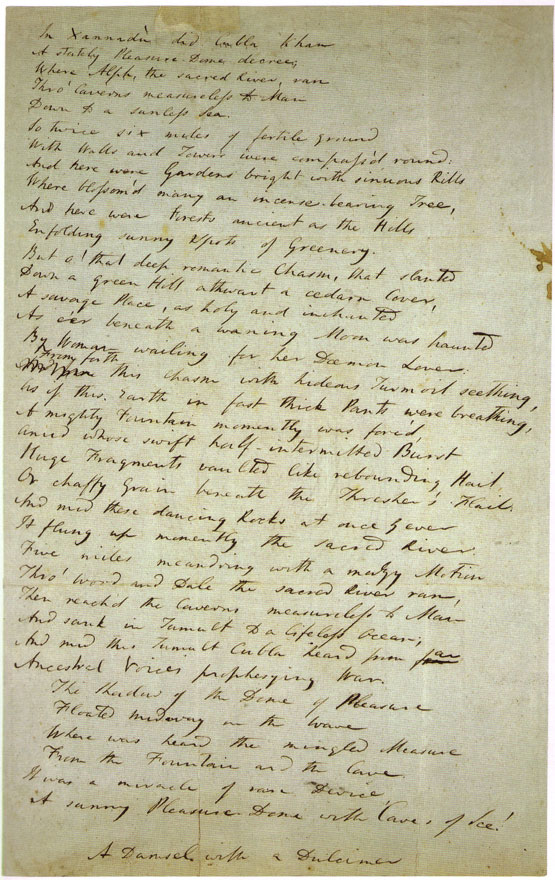

Devouring Time, blunt thou the lion’s paws,

And make the earth devour her own sweet brood;

Pluck the keen teeth from the fierce tiger’s jaws,

And burn the long-liv’d Phoenix in her blood;

Make glad and sorry seasons as thou fleets,

And do whate’er thou wilt, swift-footed Time,

To the wide world and all her fading sweets;

But I forbid thee one more heinous crime:

O, carve not with the hours my love’s fair brow,

Nor draw no lines there with thine antique pen!

Him in thy course untainted do allow

For beauty’s pattern to succeeding men.

Yet do thy worst, old Time! Despite thy wrong

My love shall in my verse ever live young.

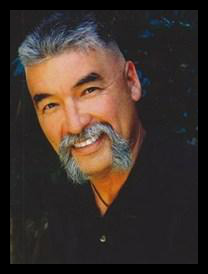

I write this post the day before my friend Scott’s funeral, the day after Easter Sunday. It is a time of resurrection, but now, at this moment, it is so hard not to see “devouring Time”, like an animal, consuming, destroying.

I knew Scott as a regular at Numbers, a nightclub I’ve gone to since I was in high school. He was a regular, and I knew him for a number of years. For a long time, he had to get around with the aid of a walker and he would sit in his spot in the club near the entrance, and I would sit by him when I wasn’t dancing, and we would talk, especially about our shared passion for movies, science fiction, comic books. I remember one of the last films we talked about was Mad Max: Fury Road. I recommended he see it, and he did, and he enjoyed it. That makes me feel good, that we could share something simple and pure like that.

What I loved about Scott was his passion for life. In that harsh and unyielding desert where he was, where he struggled with his illness, Fabry Disease, he never stopped, he never quit, he kept coming to Numbers, to be in a place that made him feel alive, and it was an honor to share those moments with you, my dear friend. I will miss you. I will always see you there in your spot, always somehow hoping you will somehow appear on those Friday nights, to sit down and talk with me about the latest movie.

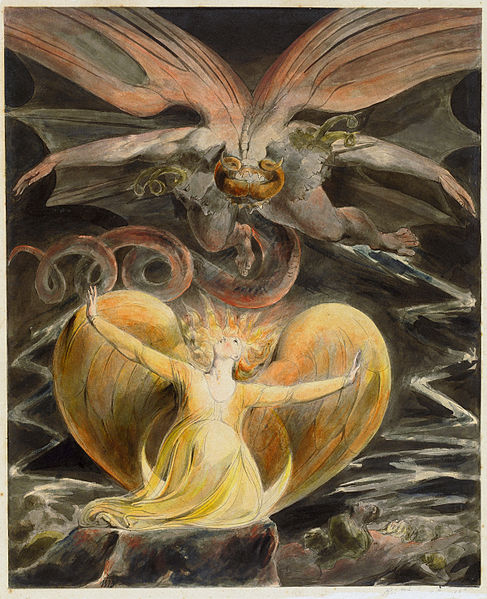

And in writing this, my own small shrine in words to Scott, like Shakespeare’s immortal lines from his “antique pen” that still burn with the embers, the fires of life, I pray that Scott will forever be born in all the lives he touched and his memory will not fade, like the phoenix, like Christ, forever risen, forever rising.

And that you are in a better place, and the music never dies.

Please share your own thoughts and responses to Shakespeare’s poetry.

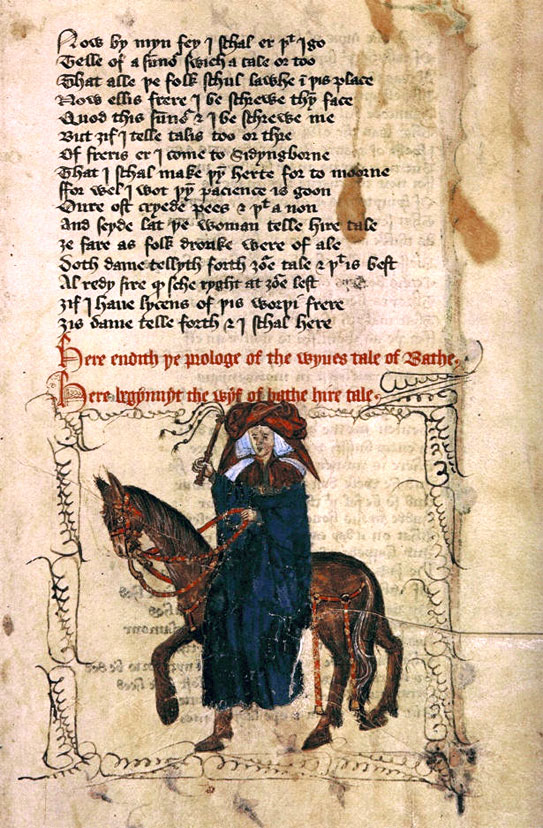

Nowhere in early British literature is there quite a character like the Wife of Bath. She dramatically bursts onto the scene in Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales and, like Shakespeare’s great characters such as Falstaff, almost takes on a life of her own beyond its pages. Her clothing itself is flamboyant: “Her stockings were all fine and scarlet red, / Quite tightly laced, her shoes quite soft and new. / Bold was her face, and fair, and red of hue” (lines 458-60). Symbolically, she has “on her feet a pair of sharp spurs poked” (475). She is passionate about life, full of fire and drink, and enjoys it to excess. Like Samantha from Sex and the City, she is powerfully in control of her sexuality.

Nowhere in early British literature is there quite a character like the Wife of Bath. She dramatically bursts onto the scene in Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales and, like Shakespeare’s great characters such as Falstaff, almost takes on a life of her own beyond its pages. Her clothing itself is flamboyant: “Her stockings were all fine and scarlet red, / Quite tightly laced, her shoes quite soft and new. / Bold was her face, and fair, and red of hue” (lines 458-60). Symbolically, she has “on her feet a pair of sharp spurs poked” (475). She is passionate about life, full of fire and drink, and enjoys it to excess. Like Samantha from Sex and the City, she is powerfully in control of her sexuality.